Healthy, Young Wildlife

Many baby animals brought to us each year are not really “orphans” in need of care. They are young animals still receiving care from their parents, or young animals that are ready to live, and thrive, on their own. If you see a young wild animal, it’s best to first ask questions before intervening. Despite our natural inclinations, the best chance of survival for a young uninjured animal is often to leave it in its parents’ care.

Assess the situation before picking up an animal!

If you have any questions, please give us a call or text first before intervening.

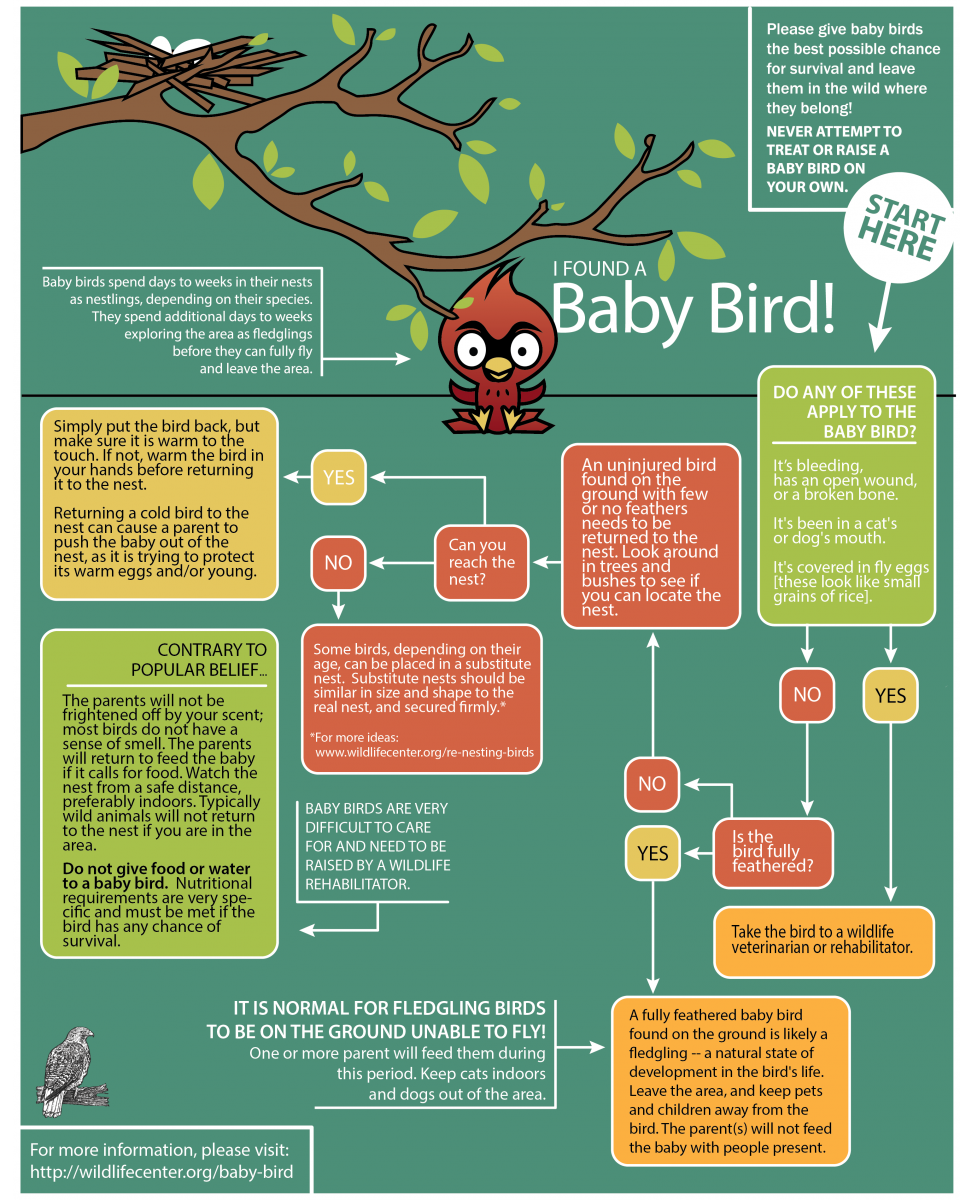

Baby Birds

It’s common for people to encounter baby birds in the spring and summer. Depending on the species, baby birds can spend days to weeks in the nest, where they are cared for by their parents. As the babies develop, they grow in feathers and get ready for the next stage of development – fledging. As baby birds take their first flights, many species stay close to the original nest, where their parents continue to care for them.

Please give baby birds the best possible chance for survival and leave them in the wild where they belong!

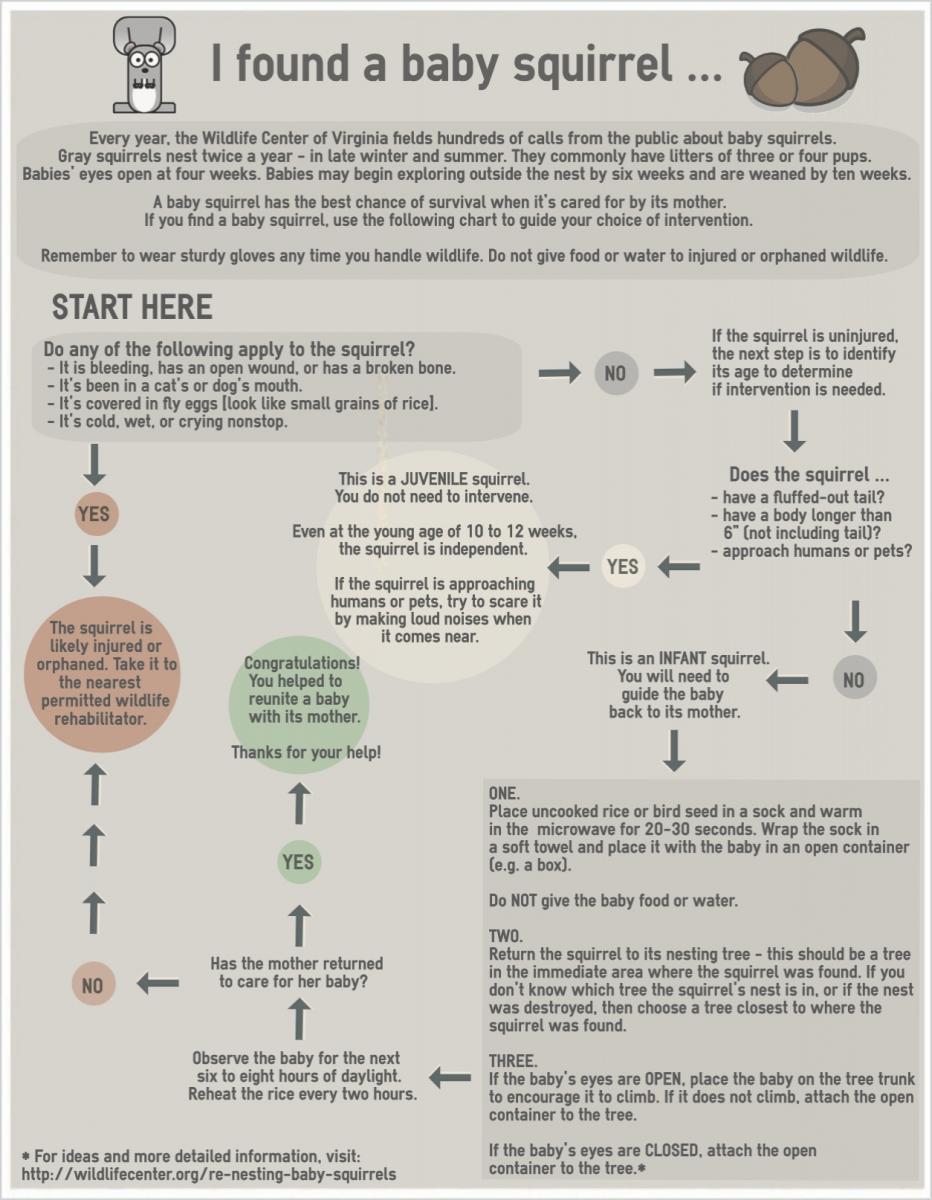

Baby Squirrels

Gray squirrels nest twice a year, in late winter and summer. They commonly have litters of three or four pups. Babies’ eyes open at four weeks of age and the young are often starting to explore outside the nest at six weeks of age. They are typically weaned and ready to be on their own at 10 weeks of age.

A baby squirrel has the best chance of survival when it is cared for by its mother. Sometimes healthy young squirrels found on the ground are not orphans — they simply need help being reunited with their mothers. Mother squirrels will “rescue” their fallen or displaced healthy babies by carrying them by the scruff back to the nest – they want their babies. We will walk you through the steps of reunification when/if appropriate.

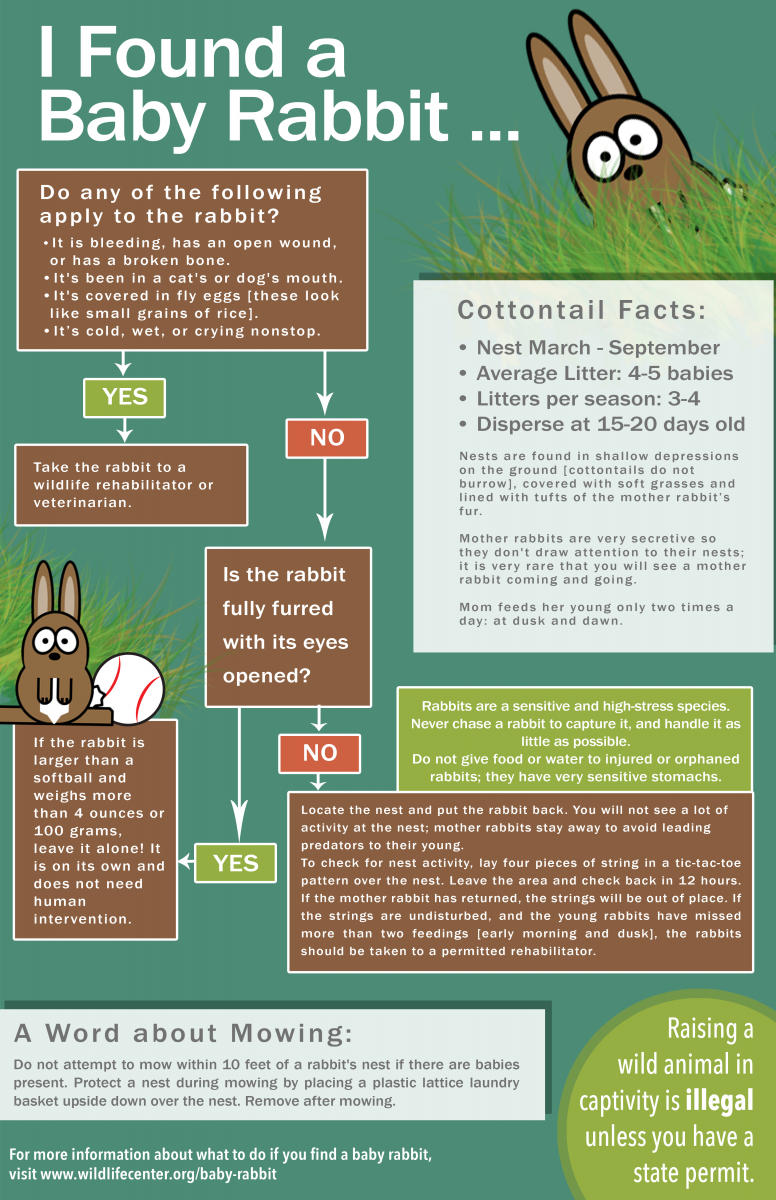

Baby Rabbits

Mother rabbits are very secretive, so they don’t draw attention to their nest; it is very rare that you will see a mother rabbit coming and going. She feeds her young only twice a day — at dusk and dawn.

Young rabbits leave the nest at 15-20 days old. By three weeks of age, they are on their own in the wild, though are still very small — they’re only about the size of a softball! Rabbits have the best chance of survival when they are cared for by their mothers.

Please give baby rabbits the best possible chance for survival and leave them in the wild where they belong!

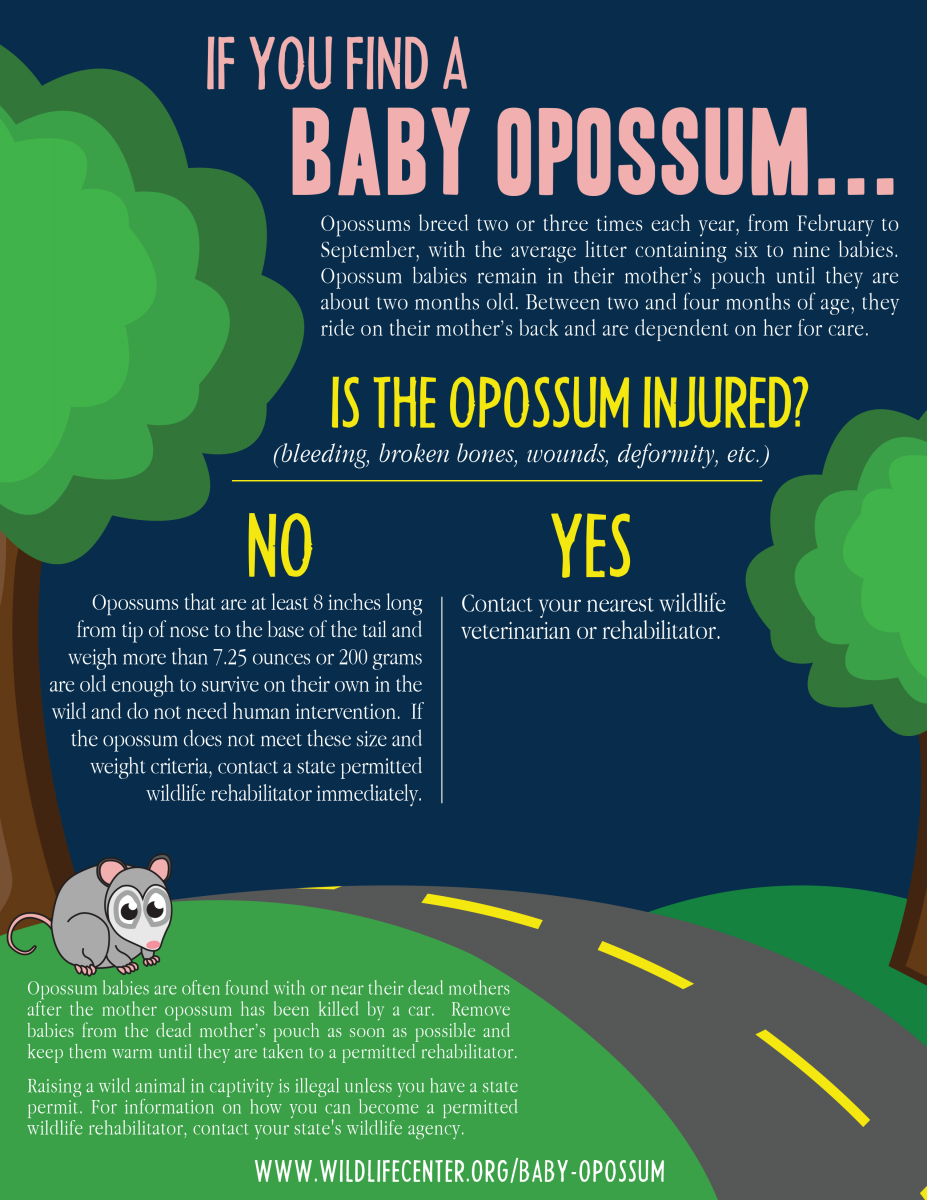

Baby opossums

Virginia Opossums breed two or three times each year, from February through September. The average litter contains six to nine babies. Opossums remain in the mother’s pouch until they are two months old. Between two and four months of age, they may ride on their mother’s back and are dependent on the mother for help in finding food and shelter. If you find a baby that is under 8” from the tip of the nose to the base of the tail, it needs assistance.

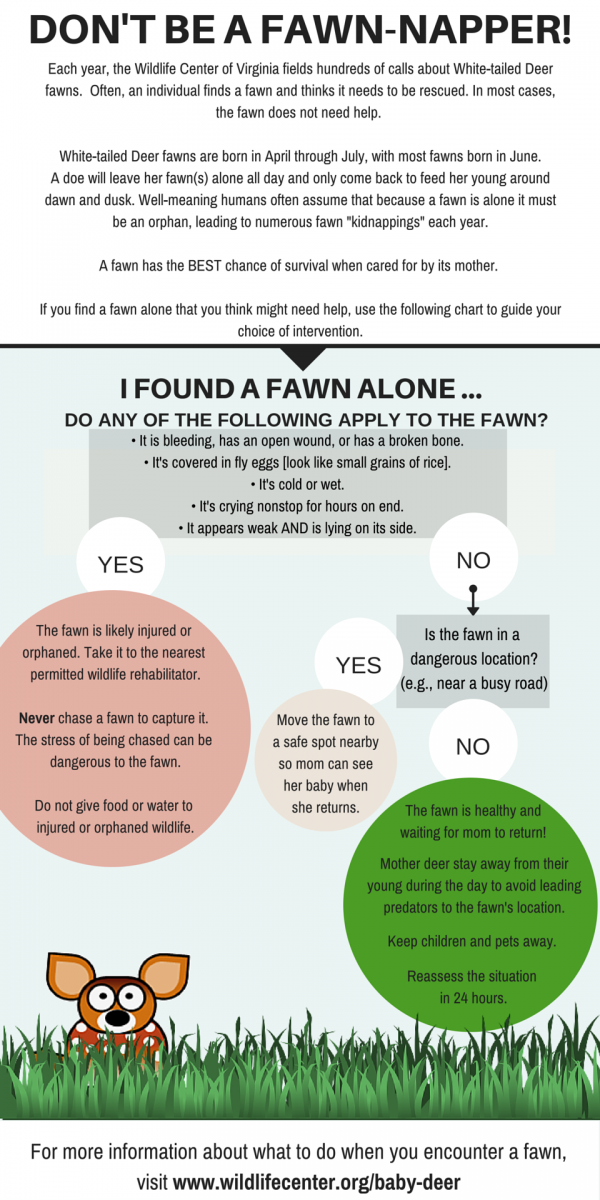

Baby Deer

Until they are strong enough to keep up with their mothers, fawns are left alone while their mothers go off to feed. Mother deer will stay away from the fawns to avoid leading predators to their young. Does return at dawn and dusk to feed and/or move their young.

Fawns are typically left in an area with tall grass or bushes, but sometimes they are left in more open areas, including backyards. Older deer fawn may wander short distances.

Well-meaning humans often assume that because a fawn is alone it must be an orphan, leading to numerous fawn “kidnappings” each year.

A fawn has the BEST chance of survival when cared for by its mother. Typically, the best option is to leave the fawn alone! Do not EVER chase a fawn as this can lead a condition called capture myopathy which leads to death.

Capturing Wildlife

An animal that has been cat caught, even if you do not see puncture wounds, is an EMERGENCY SITUATION due the bacteria in cat saliva.

Use caution when attempting to capture injured wildlife. Even a debilitated wild animals will attempt to defend themselves. Proper safety equipment (gloves, protective eyewear) should always be used. Other helpful items include blankets/towels, nets, or anything else that allows you to assist the animal without coming into direct contact. Please call us for specific rescue advice for the species with which you are dealing.

If you are unable to reach someone by phone and need to assist an animal quickly, follow these general steps, and always remember to keep yourself safe!

Remember that it is illegal for any person, other than a state appointed rehabilitator, to care for wildlife.

01.

Prepare a crate or a box for the injured animal. Line the bottom with material such as a tee shirt or fleece so that the animal can stand without sliding around.

02.

In most cases, throwing a towel or sheet over the animal works well; this helps contain/restrain the animal, and also covers its eyes, which helps reduce stress. Wearing protective gloves, pick up the animal and move into the transport container. Use extra caution when assisting mammals.

03.

Secure the container so that the animal cannot escape. If using a cardboard box, make sure flaps are secured with tape and air holes are put in the box before the animal is placed in it.

04.

Keep the animal in a warm, dark, quiet area, away from people and pets. Resist the urge to peek or take photos; while this may be an exciting experience for you, remember it is quite stressful to the wild animal – we are predators to them. Avoid talking, loud music, and other disturbing noises as well as strong scents such as cleaning supplies, candles or smoking. Unless otherwise instructed by a permitted wildlife rehabilitator or veterinarian, do not feed or give water to the animal. Food can often end up making an injured animal sick; it can also impede further treatment when a wildlife rehabilitator receives the animal.

05.

Get the animal to a permitted wildlife rehabilitator as soon as possible.